TOBY COOPER

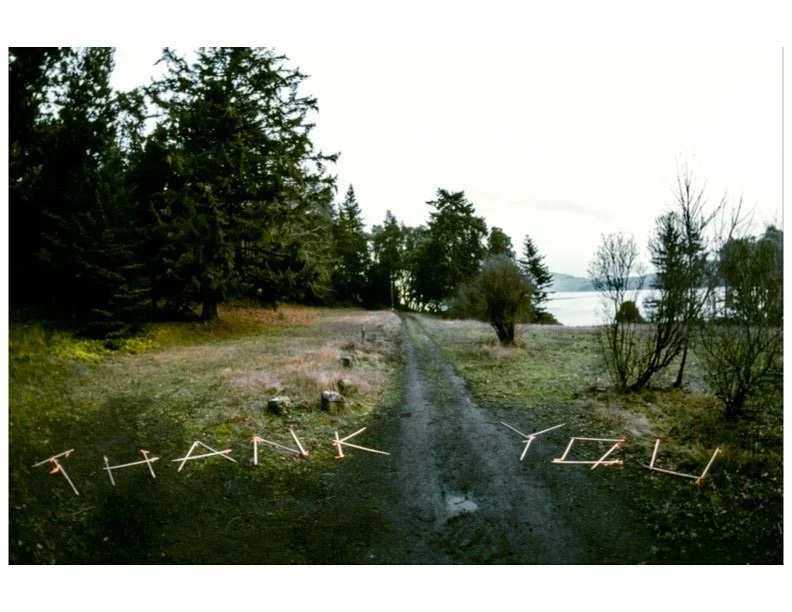

Photo by Peter C. Fisher

Madrona Point— Ts’el-xwi-sen’—is the beating heart of Orcas Island. The Lummi knew it for over 5,000 years, paddling treacherous canoe miles to bring their deceased tribal elders to the sacred place of eternal rest. James Tulloch knew it in 1887 when he attempted unsuccessfully to block the purchase by the Harrison family, who Tulloch feared was prepared to devalue the deep Lummi identity with the land. Norton Clapp knew it when he paid money for a property that he hoped others would pay him more to give up. And, nearly forgotten among the star-power, a thoughtful islander and intimate friend to William Randolph Hearst II named “Nancy,” knew it—but let us not get ahead of the story.

“If I go, you go.”

Peter C. Fisher contemplated the sound of those words for a moment, allowing them to soak deep. Part prophecy, part threat, but every ounce a clarion call to action, Peter knew his life was about to change. It surprised him not at all that when he heard those words, he was alone among the trees on Madrona Point.

The year was 1984. “I heard that the Point was going to be developed,” Peter remarks as if it all happened last Tuesday. “I went out there with my camera, and the land spoke to me. There was no turning back.”

But Peter was not alone in his mission. “It was about power and place, and the power of place,” he says today. Eventually, that power stretched from Eastsound to Washington, DC, from Peter’s study of the Nantucket Land Bank to the halls of Congress, from the San Juan County Council to the elders of the Lummi Nation. In the end, it was the confluence of remarkably synchronized actions by an unlikely collection of complete strangers, all inspired by the undeniable spiritual power of 30 acres of trees.

Some secrets Madrona Point still holds. Long assumed a place of traditional burials, one legend holds that bodies of the most revered ancient Lummi elders were elevated into the trees, where weather and scavengers and time itself would render them to the Earth.

Now, as then, the big firs stand erect and proud, like diplomats at a reception, drinks in hand, exchanging imperceptible nods of recognition. They converse in low tones, wishing for rain but remaining unperturbed when there is none. Pallid bark etched by storms, yearly cone crops adored by squirrels, they ask nothing more than to be left alone on the timeless shores of the Salish Sea.

But the sylvan Madrona’s grab all the attention. Since the groves of fir beat them to the best ground, they reach sideways for sunlight over the salty rocks at the water’s edge. They are the unruly group at the kids’ table. Their improbable, perpetually peeling red and green trunks twist about in a riot of movement that mocks the stately firs. And yet, it is their essential beauty that inspires memory, passion, and action.

Listening to the land in 1984, Peter Fisher’s first and ultimately pivotal act was to create a magnificent 28-foot collapsible accordion-style rendition of his best Madrona Point photographs, published in a single uber-limited run of seven hand-crafted volumes, on premium sale for $2500 each. Sales were brisk enough to fund the wider campaign to save the point, including rousing public meetings and hearings, but by September of 1989, the Orcas community faced a classic binary choice, save Madrona Point, or let the laissez-faire economic forces dictate the outcome. Saving the point, of course, meant someone otherwise in line for profit would need to be compensated. And that price tag would be millions.

The chainsaws were literally poised to snarl. Desperately needed was just one tiny, indispensable link to connect five years of inspired grassroots action on Orcas with the fearsome political potency that is Washington, D.C. Like the light switch on the wall or the neck in the middle of the hourglass, such links are the difference between movement and utter stagnation. Here, that link was Nancy.

With no fanfare or public pretense, Nancy, with the honest passion that Orcas Island seems to inspire in all who step ashore, inspired her good friend William Randolph Hearst II to hastily enroll himself as quarterback of the effort. Hearst took his mission to heart. He bought and packed the last three accordion books on a flight to Washington, D.C., and in remarkably efficient fashion won unanimous Congressional approval for a $2.2 million Interior Department appropriation to buy Madrona Point, transfer title and management rights to the Lummi and set in place a timeless conservation mandate to protect the fragile forested point.

Madrona Point still speaks. The land reminds us daily that we—the Lummi, the county supervisors, the gaggle of summer tourists, all of us—are not owners but guests on this green Earth. When we work together, we can accomplish great things; Peter Fisher reminds us that our community’s passion for saving the point led directly to the formation of three lasting and respected island institutions, the San Juan County Land Bank, the San Juan Preservation Trust, and the OPAL Community Land Trust. Only if we listen to the land and to each other do we enjoy such winnings. And then only if we live lightly enough so as not to upset nature’s foundational underpinnings that permit us to remain do we give ourselves the chance to win.

The beating heart of Orcas Island speaks to us all.

My Life With Birds

Rasty

The fledgling bird sat googly-eyed in a shoebox, oversized feet splayed like a deer on ice, unafraid, unphased, and obstinately ignoring his surroundings.

“Only a mother could love,” I thought. “At least, a mother crow.”

That was the Spring of 1972. The Earth was cooler then, less festooned with plastic, and according to experts there were billions more birds in those days. Quite unexpectedly, one of them had shouldered into my life. Neither of us knew it yet, but we were about to share a time of love, adventure, discovery, and pivotal change.

Now, if birds are your thing, crows are a special case. Crows are smart. They live socially, always hang with family, solve tricky problems with ease, and seem to possess an uncannily human sense of humor. The bird in the shoebox would prove the truth of all these claims – and more.

“Rasty fellow,” said the youthful man holding the shoebox, one of my college biology students at the time. He had been helping someone with tree work and rescued the bird when a falling limb brought the nest to the ground. Only this one nestling had survived.

“Rasty,” I mused with quiet reverence that was quickly morphing into voluble adoration. “Hello, Rasty. Let’s get you something to eat.”

If you are going to raise a crow, being a biology teacher is your best bet. You have access to lots of useful biology-lab stuff. There are bins of nutritious animal food in the basement, and the developing bird becomes a living case history in avian life cycles. But most of all, for people around you who do not really get the bird part, your career gives you cover.

It took Rasty only a few hours to peg me as a surrogate crow-dad and an open-ended source of yummy things to eat. I secured a supply of kibble-style Gaines Dog Meal – then a quality brand that has since been broken into parts and assimilated by processed-food conglomerates. But this young crow flourished on the original Gaines’ recipe consisting of high-grade beef, bone meal, liver, zucchini, kale, seaweed, and lots more of what an omnivorous wild crow might want to eat anyway.

Initially, Rasty made his home in my office, visited, predictably, by a steady stream of biology students who ducked in between classes to marvel at the bird’s progress. They brought him bugs and worms to supplement the Gaines pellets. He voraciously consumed everything, squawking and pooping on a 45-minute cycle – conveniently timed to the approximate class lecture schedule. With steady progress, feathers grew to cover his naked, pink contours, and he swiftly gained strength and coordination.

For my part, I swirled into the unfamiliar universe of proud parenthood.

I never thought of Rasty as a pet. He was never caged. Pets are love you can buy, creatures we seek for entertainment, companionship, and instant gratification. No, Rasty was a wild crow who made the decision to run with the human crowd for a while, and he knew exactly what he was doing.

Part of Rasty’s appeal was the compressed time scale of his transitions. He phased through recognizable developmental stages including dependent infant, awkward adolescent, experiential teen, and poised adult, each in a matter of a week or two. Sometimes it was hard to keep up.

One spring day when Rasty was yet a stumbling adolescent, I took him out on the lawn in front of the biology lab. As he began to stalk about on the grass, I stretched out to get my face right down to his level, to try seeing the world through the eyes of a crow. I was lost in the wonder and bird-world magic of the moment.

Just then, one of my students came along to lobby me about her grade, which was suffering. Big mistake. This was Rasty-time. His pattern on these outings was to periodically hop in my direction to beg for food. But suddenly he veered off and snatched up a fat, green cicada – those inch-long insects that make buzzy sounds under the hot Midwestern sun. He shook it once and gobbled it down like a pro. It was his first self-earned meal.

I was ecstatic. Forgotten was the co-ed’s brazen appeal for the gift of a passing grade. How shallow her effort suddenly seemed, attempting to sidestep the same self-driven path to achievement that a crow on the grass had just so convincingly demonstrated. For Rasty, college was but a banal distraction from the real stuff of life.

That crows seem to possess a mischievous sense of humor is not in scientific dispute. British naturalist Gerald Durrell published accounts of his captive magpies – close relatives of crows – who learned to deliver a perfect imitation of Durrell’s maid’s call to summon his chickens to feed. The magpies would get bored, call out once, and the chickens would come running. Finding nothing to eat, the chickens would wander off, only to be called back again. No matter how often the magpies repeated the trick, the chickens fell for it every time.

By the time Rasty had the run of the campus, his particular brand of snarky humor began to emerge. He targeted students doing homework outside, stalking up to them in a feigned posture of gregarious goodwill. “Oh, hi Rasty,” the hapless victim would proclaim. In a flash he would snatch their pencil right from their hand, fly to the roof of the admin building, peck the pencil maybe twice, and then fly off to find something else to do.

It got better. Rasty’s favorite trick was the Sneak Attack. He would position himself on a roof near a sidewalk and wait patiently for a sucker to pass by on a bicycle. Patience was key. He would let the bicycle go on by for three, maybe five seconds before spreading his wings and, gliding from behind in swift silence, would bang the kid on the head with both feet. Some students and most faculty began to plan their bicycle itineraries specifically to avoid Rasty’s known venues for attack.

Gradually, the inevitable backlog of complaints began to reach the biology department headquarters. For sure, Rasty thought he was funny. I certainly thought he was funny. And a few of his partisan friends thought he was funny. But crow-humor goes just so far in the broader community.

Eventually, the Dean of the College summoned me in for a conference. It seems one of the secretarial assistants had a genuine phobia about birds that fly through the air and might bang her on the head while she was on her way to lunch. Accordingly, she had not eaten lunch in weeks. To get to her car after work, she would wrap her coat around her head and run for her life, shoes in hand, ruining one pair of nylons per day.

I was mortified. How could anyone suffer from “bird phobia” when birds were so cool. Rasty was placed on probation, whatever that means for a crow. Fortunately, the school year was winding down and the promise of us both “moving on” was seen as the best compromise.

That June, I packed my books, files, clothing, and remaining worldly possessions into my VW bus and headed west across the prairie states. I fleetingly imagined we were reenacting Steinbeck’s 1962 classic Travels with Charley: In Search of America in which Steinbeck and a poodle seek to define the nation they both loved. Rasty rode on the dash without a care in the world, as if cross-country road trips were a normal part of any crow’s life.

Two days later, we entered Wyoming, and the overloaded bus labored to the Continental Divide.

With some trepidation, Rasty and I arrived at the gates to Grand Teton National Park. Driving around with a crow in the car is in technical violation of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which prohibits the “killing, capturing, selling, trading, and transport” of crows and other birds without “prior authorization by the US Department of the Interior.” No problem. We paid our fee and the ranger gave us a map.

We were there to rendezvous with Steve, a college friend who was just back from two tours as a Naval officer in the Viet Nam war, and who himself had once served as a park ranger in the Tetons.

Months earlier, Steve and I had planned this trip. It proved to be exactly what we both envisioned – a therapeutic cleansing of the psychic wounds from a conflict the nation would likely never understand.

We laid out an ambitious three-day hike up one of the canyons – nothing out of the ordinary for a couple of 20-somethings loaded with REI gear. Unknown, of course, was how the crow would blend with the project. I packed a supply of Gaines Meal, and we headed west on the Granite Peak Trail.

I had imagined Rasty would ride on the top of my backpack, not unlike his perch on the dash of the minibus. But he would have none of it. He flew to a trail-side tree, let us go for a while, then caught up, landing in another tree just ahead. He leapfrogged our progress like that, mile after mile. Whenever we stopped, I would soak some more Gaines. We kept this up for three unforgettable days.

Did Rasty complain? Oh, yes, he did. Our trek was indeed ambitious, calling for some 20 miles the first day. Towards the end, Rasty started getting tired. I was getting tired. Steve, fresh from the Navy, was powering. Rasty started landing closer to me on each leapfrog leg. He would kind of slam down on a branch with body language, saying, like, “OK, guys, let’s knock off now.”

To which I would respond, “Who’s carrying your dinner?”

On balance, backpacking with a bird was a marvel. He was as loyal as any puppy dog. At night, he would roost in a tree by the tent, rousting us out at sunrise. His food weighed almost nothing. He was a joyous companion in a wilderness that was far more his than ours.

Truth be known, this was an uncertain time in my life. The teaching appointment at the college had been temporary by design, so I would not be going back. I had some savings, no debt, the luxury of time, and was enjoying the search of the next chapter of my life.

The road led to Northern California. I had landed a job interview with the non-profit Point Reyes Bird Observatory and on the way back, stopped at Stinson Beach. There, stretched before us, was the eternity of the Pacific Ocean.

Rasty, fresh from the Illinois flatlands, was transfixed. I let him out of the car – my heart in my mouth. He flew straight out over the surf line, expertly managing the wind. I forcibly squelched a moment of panic, reflecting that Rasty “has never really seen water that was not in a dish.”

He cut one tight circle over the surf and then decided he just had to test this extraordinary, heaving landscape. He settled low. Reaching down with one foot, he touched the salt water once, then again as a Pacific swell surged up towards him. For all the world, it looked like he would drop right into the water. But, nope, not going to die today. He flew back and clutched my arm, gasping with excitement.

“You just figured out the ocean,” I said aloud.

The promise of another teaching job led me to the progressive and very new campus of the University of California, Santa Cruz, where one Dr. Richard Cooley was planning a visionary Environmental Studies program. Cooley was optimistic that funding for his Earth Day-inspired program would be approved later that year, and I was invited to come back then. In the meantime, he suggested that I visit the Alan Chadwick Farm and Garden project on the lower campus property.

Rasty and I rolled down the hill to investigate – a decision which changed our whole trajectory.

The UCSC farm project had recently been launched by pioneering organic gardener Alan Chadwick. Originally conceived as a working farm to demonstrate “French Intensive” farming and provide a platform for research, the idea was a huge success. Over the next 50 years, the humble project would mushroom into a sprawling institution known as the Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, and would become an umbrella for dozens of affiliated faculty and hundreds of students.

What I found that day in July, however, was a handful of hippie farmers with big hearts, dirty feet, and unlimited supplies of fresh zucchini.

The farm property was idyllic. Meticulously-tended raised garden beds graced the golden slopes, which in turn were peppered with Redwoods and spreading oaks. To the South, the blue mistiness of Monterey Bay beckoned with dancing whitecaps, backed by the looming grandeur of the Monterey Peninsula 26 miles away. Open-air farm structures were hand-crafted of heartwood, delicately accented with wind chimes and stained glass.

The dozen-or-so kids on the farm (Pharm Phreaks, they called themselves) welcomed me and my bird friend as a novelty attraction. Most of them had grown up in the suburbs, dropped out of school, and dumped America’s Chevrolet lifestyle to better align with the Whole Earth Catalogue.

I set to work with a small carpentry team, building a long-house barn using resurrected Amish mortice-and-tenon joinery techniques. I learned precision woodworking with razor-sharp chisels, soon earning their trust. We camped with them for the rest of the summer.

Rasty was delighted. At last, we had stopped trucking. He investigated the property and hung out with colorful Acorn Woodpeckers. Most of all, Rasty loved “helping” people with busy hands, and on an organic farm, everyone’s hands are busy.

French Intensive farming is labor-intensive. Vegetables are sprouted from seed, in flats stacked on outdoor shelves. As the shoots grow, they are transferred into larger flats until, finally, they are carefully extracted and row-planted in the freshly-tilled garden beds. This was the stage at which Rasty was most fond of helping.

Ah, the Achille’s Heel of a home-grown crow. As we know, Rasty was already a college-trained pencil snatcher, and as the weeks went by, he perfected his craft to address pencil-sized vegetable sprouts. As fast as the hard-working Phreaks could plant zucchini shoots in the ground, Rasty would stalk up to the bed behind them and yank the whole row out of the ground.

I knew what was coming, of course. It was not funny anymore. Mere college deans with bird-phobic secretaries could not compare to angry organic farmers with virtual pitchforks and torches. The normally tolerant and inclusive Pharm Phreaks had hit the limit and I knew something had to change.

But, how do you reason with a crow? I honestly believe Rasty understood the word “no.” He just declined to comply. It is all so easy when you have wings; when the going gets tough, the tough fly away and come back later.

I sat with the bird in one-way conversation – futile, by any stretch. By now it was August and Rasty had finished molting his dusky juvenile feathers. He looked splendid, glossy, streamlined, irresistible. “You are a resourceful bird,” I concluded, “so instead of fighting, let’s use that to advantage.”

And with that, a solution appeared like a light in the foggy night. In the morning, I collected my things, promising to return. I climbed in the van, Rasty hopped in with me, and we headed South on Highway 1.

Carmel-by-the-Sea, Point Lobos, Bixby Bridge, Big Sur – the coastal splendor of California was on full display all day.

At San Simeon, we pulled into the turnout for a break.

I let Rasty out of the car for his usual stretch. But this time, something about the moment – the blue sky, the expansive vista leading upslope to the distant Hearst Castle – unlocked a curiosity he just had to satisfy. He launched into impulsive flight and started winging energetically up towards the castle.

Fearing the worst, I watched in dismay. This could be a long stop. The moment became a blur. Then dismay turned to horror as Rasty, now but a black speck against the wide slopes, suddenly found himself in the bombsights of a fast-moving Red-Tailed Hawk.

The hawk did what hawks do well – stretched to gain height over Rasty, who to my supreme relief, fought back instinctively by trying to climb above the hawk. They swirled like this for an eternity, as I watched helplessly from the road below.

Suddenly, Rasty seemed to remember he had a trump card to play. He broke off the climbing contest, did a backflip turn and with wings folded tight to his body, barreled back down to the car. He zipped directly through the open door and landed on a box of books, quivering and panting, but safe.

I shut the doors, pointed the bus South, and stepped on down the road. Rasty recovered his composure – a little older, more than a little wiser.

The hawk, foiled like the coyote in a Roadrunner cartoon, presumably went home hungry.

The final chapter of my life with Rasty unfolded in San Diego. I had family in nearby La Jolla, which created a double benefit for the trip south.

Rasty, determined to inflict one more episode of consternation, immediately became confused in the unfamiliar seaside town and went missing for two days. I found him completely by accident, two miles away on the sands of Mission Beach, where I spotted him from a distance, surrounded by a gaggle of sub-teen kids.

I could hear them arguing, “He’s mine.” “No, he’s mine.” I walked across the sand. Rasty spied me coming and immediately flew to my arm. “Looks like he’s mine,” I said to the astonished kids and walked back to the car.

The next day, I fulfilled the plan that had come to me in Santa Cruz. I had always enjoyed visiting the San Diego Zoo, a remarkable institution spanning 100 acres and home to over 12,000 animals. Many are housed in open-air pens, with all kinds of scientifically-certified food preparations right out in the open. Parrots and other wild birds move about the grounds freely. My mother was a dedicated member of the supporting association.

Potentially, Rasty could simply blend in. It seemed like a genius solution – at least for a while.

I drove us to the Zoo, pulled into the parking lot, and opened the car door. Rasty did exactly what he had done so many times before – high-tailed directly towards the intoxicating sights and sounds of something new. I watched him disappear and then drove away with a dreadfully heavy heart.

On one hand, awesome plan – premeditated and virtually bullet-proof. On the other, what a stinker. Rasty buzzed off without so much as “thanks for the ride.” I knew I would miss him to the bottom of my soul. He would surely miss me, too.

Fast forward three or four years to a strikingly different time and place. I had a wife, a career, and a life in Washington, DC. My peripatetic year with a witling crow had receded into one of those memory banks one stores for all time, always accessible, but not quite in the front row.

One day, the mailman brought an envelope from a former student I had known during the year of teaching college biology in 1972. Inside was a page torn from The Christian Science Monitor, apparently from the soft-newsy part of a weekend edition. It covered the story of a crow who had befriended a bunch of kids in the Point Loma section of San Diego. Allegedly, the bird enjoyed playing baseball and other games.

Point Loma is four miles from the San Diego Zoo. Could it be? No, wrong question. It had to be! What pure magic this was.

A wave of emotion swept over me. Calling it “nostalgia” would not do it justice. I conjured up a million memories of an insouciant black bird who not only accompanied me through a bevy of metamorphic moments in the crossroads of life, but who in fact seemingly pointed out which roads to take. For another hour, I explored the viability of an impulsive “red-eye” flight to San Diego, until reason finally prevailed.

Instead, I contacted the editors of the Monitor and told him my story. I asked them to forward my name to the reporter who had written the piece, if only to see what additional context I might extract from his interviews.

The author never called.

###